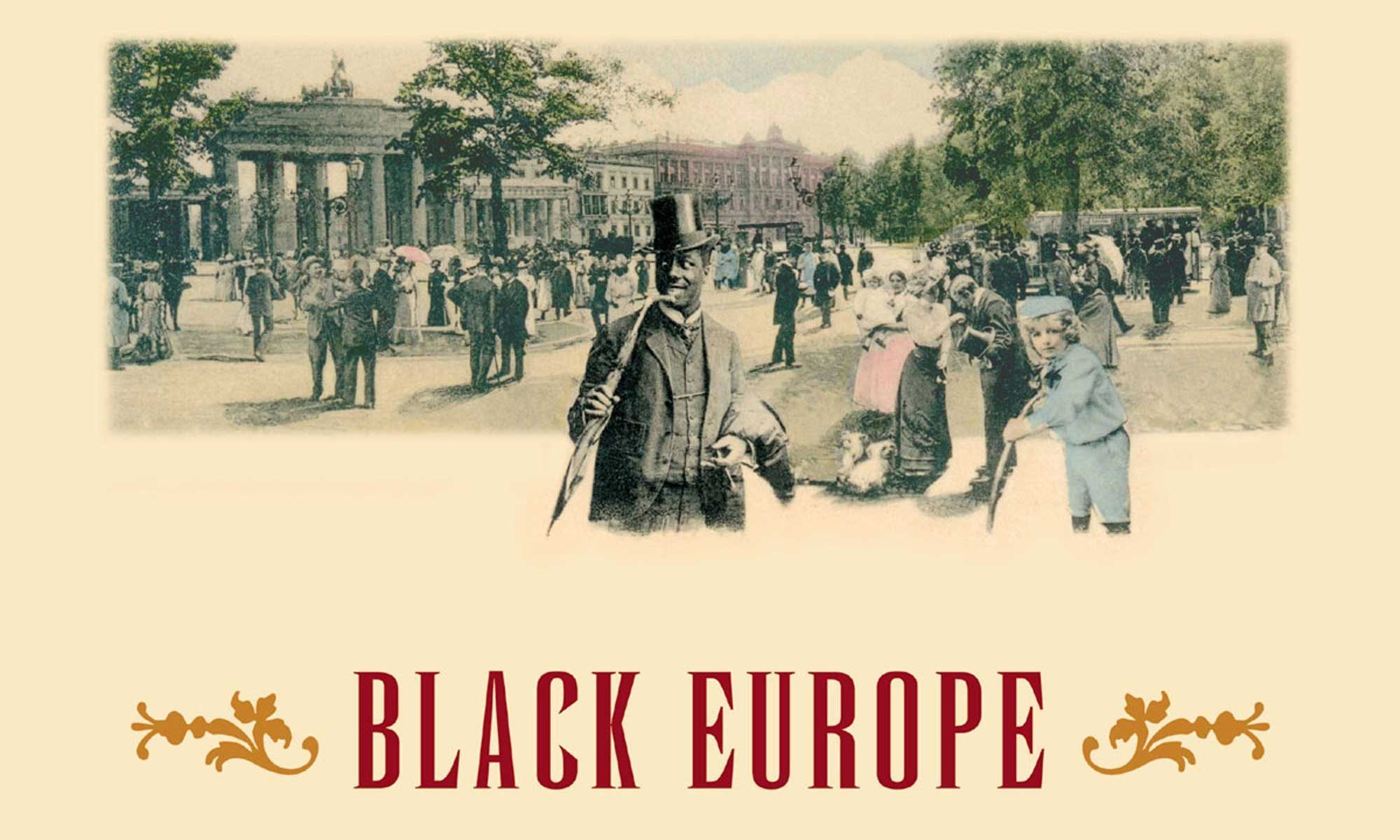

BLACK EUROPE – BLACK EUROPE

BLACK EUROPE – BLACK EUROPE

Fascinating archival trawl through the first stirrings of Europe’s black culture

There are many strands to the migratory presence of black Africans in Europe, which go back to the Greek and Roman empires, and the 1600s, when Portuguese navigators captured Africans from their native lands to be sold as slaves along the southern coast of Europe. Slaves from the West Indies were brought in to work in shipbuilding and mercantile industries.

Black figures featured in European paintings as early as the 1400s but Chevalier de St George, who died in 1799, was the first black African to compose musical scores in the classical European style, finding widespread fame as the Black Mozart. By this time, black immigrants could move freely across Europe, a situation far different to that in America.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book that stereotyped black people as loyal servants and picaninnies, led to various stage versions that boasted “real” black song and dance performers. The self-deprecating humour in these shows was apparently “very pleasing” to a white audience. Black minstrelsy had surfaced around 1830, when performers began to display a more indigenous form of song and dance in theatres and music halls throughout Europe, while “beach” entertainers became a spectacle at coastal resorts. A minstrel group’s instrumentation would often consist of “bones”, played like castanets, a banjo and perhaps a fiddle, and a small drum called a “tambo”. A newspaper report from 1847 described minstrel music as “negro melodies – the very democracy of music”. The minstrel tradition persisted well into the 1960s in a development known as “blackface”: white performers who originally “adopted the negro manner” and used burnt cork as a means of “blacking up”.

The Mastadon Minstrels was one of the most popular touring groups of the 1890s. Its members performed with a full brass band and were, in their own now regrettable words, a troupe of “jolly coons” from Virginia. Also in the late 1800s, another group called the American Troubadours performed in Hamburg, specialising in humour and a cappella songs, including a rendition of Home Sweet Home.

Earlier still, in 1858, the Mc Adoo Jubilee Singers, from North Carolina, had toured Europe. This troupe was noted for having “a variety of rhythms” on offer and was largely responsible for introducing spirituals to the Continent. Spiritual singing was completely new to this part of the world and it soon became an inspiration to white composer Coleridge Taylor, who adapted the style for his 1905 overture Twenty Negro Melodies For The Piano.

At the end of the 1800s, the general acceptance of spirituals attracted the fledgling recording industry to the commercial possibilities of intrinsic black music. The first recordings were produced on cylindrical discs; but spiritual records came second place to the even more admired folk and humorous novelty songs. There were still relatively few black people in Europe at this time: the music was popular in music halls, but achieved poor sales on record.

The first all-black show in Britain, In Dahomey, was staged on 16 May 1903, at the Shaftesbury Theatre in London. It featured sketches, music and dancing, and set a precedent for black revues in the coming years. This was followed, in 1906, with a black-only cast in a full-length musical comedy called A Trip To Coontown. During the 1920s, the so-called Jazz Age, dance played an even more important role in black performance, where the music for contrived routines such as the Turkey Trot, Black Bottom and the Cake Walk became a sales opportunity for both recordings and sheet music. Jazz went hand-in-hand with being black, and popular composers wrote razzamatazz numbers influenced by the good-time elements of the music. There was, however, a common assumption that black musicians were still locked in minstrelsy, playing “plonking” banjos and whining saxophones, but this was far from the truth.

Josephine Baker, from St Louis, USA, was the most important black personality to emerge in Europe during the Jazz Age; she found America to be too unappreciative of black artists and came to live in Paris. She featured at the Folies Bergère in the 1925 Revue Nègre. Scantily clothed, teasing with ostrich plumes while performing an exotic dance routine, Baker quickly became the talk of the town. Known by several epithets – including The Black Venus – she remained a celebrity in Europe until her death in 1975.

Strangely, the French adoration of Josephine Baker was not shared by the British, who regarded her as a distant name. In any case, at that point, black people in Britain were fundamentally looked upon as a subservient underclass rather than a curiosity, unlike in France.

In 1952, a pianist and member of The Jubilee Singers named Mrs Myers sang at the Royal Festival Hall in London, where she performed a programme of spirituals including Deep River, Wade In The Water and I Want To Be Ready, before an audience that included King George V and Queen Mary. Mrs Myers later toured France, Italy and Switzerland.

Live performances by gospel troupes such as The Jubilee Singers went some way to introducing Europeans to the blues. This was a fresh musical experience in early 50s Britain but it created enough public interest for record companies to begin reissuing American “race records” from the 1920s and 30s. Folk and blues artists, Leadbelly, Big Bill Broonzy and gospel singer Rosetta Tharpe, were especially popular in the newly formed market. Spirituals also filtered into the folk repertoires of some more commercial singers of the 50s, such as Harry Belafonte and Odetta who, thanks partly to their Christian message, were invited to tour Britain and continental Europe on numerous occasions. Black music in these places, it seems, had finally reached a kind of mature acceptance.

Running to 44 discs and with two generously illustrated hardback books, this exhaustively deep and fascinating musical and visual history of black Europe charts the rise of a broad musical culture and is limited to an edition of 500, retailing individually at €499.